From Marrakesh to the sea by bus!

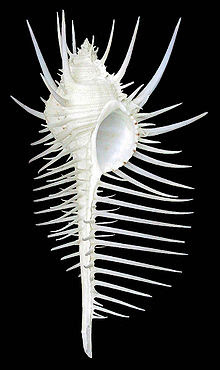

From Marrakesh to the sea by bus! Essaouira is the goal - the coastal town that done good in the 1st century BCE by providing the purple dye that was so sought after for the Imperial Roman Senatorial togas. This dye is created by processing the spiky snails and purple shells that live near the Essaouiran coast and the Iles Purpuraires. The authentic method of creating this specific shade of purple remains, to this day, a secret shared only between master and apprentice.

The snails and shells are also secretive in their location in the intertidal rocks. I was not quite sure what "intertidal rocks" were - finding out that they are a part of the littoral zone, the shifting space that appears at low tide and is underwater at high tide. (What the littoral zone is, however, has no single definition. Where it begins and ends and the subregions that it can include is argued over by Navy commanders and marine biologists.) But the littoral drift creates a microclimate for the snails who have adapted to their ever-moving home. Wikipedia goes on to share that this harsh environment "supports typically unique types of organisms."

It seems inspiring to me that these snails - these unique organisms who have managed to avoid overt commercialization after their Roman exploitation, have managed to survive throughout the centuries in such volatile conditions.

Essauouira is full of metaphors of what we do in order to survive. My favorite story is of the architect for Essaouira's city walls: Théodore Cornut, a French mathematician and military architect of the 18th century. He was captured and enslaved, obtaining his freedom only when he had finished designing and building, with the help of his fellow prisoners, the port walls commissioned by Sidi Mohamed ben Abdallah. Incidentally, in an interesting commentary on karmic colonialistic correlations, he used the same blueprints which he had used when building Saint-Malo, the walled port city of Brittany in Northern France.

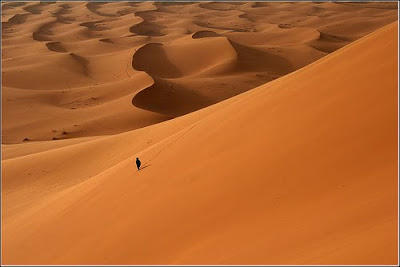

Through these travels though - from bus to books to so many different places - I am hoping to shift from survival to joy.

.jpg)